Shaping the Future of Senior Living Through Design and Research

Reimagining Spaces for an Ageing Society

The way housing and community spaces are designed plays an important role in how societies support seniors to age with dignity, independence, and purpose. In Singapore, where more than 21% of the population will be 65 years or older by 2026, this demographic shift demands new approaches to the built environment. As co-living gains traction, there is rising interest in adapting it for senior communities. This presents an opportunity to reimagine how design can foster inclusivity, resilience, and well-being in an ageing society.

Building on this imperative, CPG’s Design & Research Office (DRO) has undertaken research into how senior co-living developments can foster social well-being and support healthy ageing by focusing on the design of common spaces, circulation spaces, and interfaces within a residential complex. The findings are presented in DRO’s research publication Design for Senior Co-living. Insights from this research are distilled into a practical design toolkit that architects and planners can apply across different scales and typologies of urban co-living developments, with a focus on health, well-being, and integration with greenery and nature.

Shaping Tomorrow’s Architects with Today’s Research

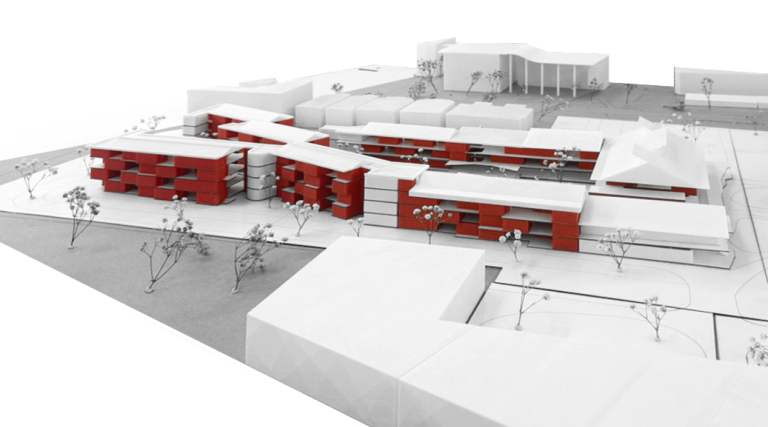

The timeliness of this research was underscored earlier this year when Ar. Pauline Ang, Director of DRO, led a design studio at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD). The studio challenged students to rethink co-living typologies for intergenerational communities, encouraging them to consider how communal housing models could foster cross-generational interaction, active ageing, and a stronger sense of belonging. Students examined case studies of communal living from diverse cultural and historical contexts, studied how different spatial configurations balance privacy with social interaction, and developed adaptive reuse strategies for old school buildings in Singapore. The goal was not only to explore architectural form, but also to propose socially grounded interventions that enrich both individual and community life.

“Expanding upon our earlier research into the adaptive reuse of common building typologies, we were interested in how old schools could be repurposed to address one of the most pressing needs of the nation – providing more housing options for our rapidly ageing population. The SUTD design studio provided an opportunity to test the potential of various design concepts without being overly encumbered by economic and regulatory constraints.” – Ar. Pauline Ang, Director of Design & Research Office

At the conclusion of the studio, Pauline invited Ar. Peter How, Director of Design at CPG Consultants, to join the Final Review panel to provide his views on the students’ work. For Peter, the theme resonated deeply. When he first joined Singapore’s Public Works Department (PWD) in 1981, the national priority was to build schools to meet the needs of the baby boomer generation. More than forty years later, many of those schools now stand underutilised, while the nation faces a new priority: providing housing and support for that same generation as they grow older.

Both Pauline and Peter highlighted the potential of repurposing schools for senior living. Many of these buildings are structurally sound, centrally located, and organised around modular classrooms that lend themselves to adaptation. With a number no longer in use, converting them for assisted living becomes a natural option, and there is a poignant thought of a baby boomer returning to the same school of their childhood in their golden years.

Research Breeds Imagination: Reframing Senior-living

Reflecting on the SUTD studio, the panel remarked that exploring senior co-living through both research and teaching is valuable in addressing Singapore’s broader need to reimagine housing models for an ageing population. “Many recent senior co-living projects tendered by the government have been bound by short lease durations, which naturally restrict the extent of design interventions possible. In contrast, the academic exercise was freed from such commercial constraints, allowing students to explore bold and imaginative possibilities,” the panel noted.

Rethinking Corridors

While the typical classroom block lends itself well to adaptive reuse, the corridor is usually retained for practical reasons, which makes it difficult for it to shed its institutional image. One student proposal challenged this by gutting the block, keeping only its structural frame and slab, and inserting housing modules in irregular clusters linked by interstitial spaces. This removed the monotonous corridor, creating privacy while also encouraging bonding between neighbours.

The review panel noted that although such drastic interventions may not be commercially viable, the concept highlights how the corridor can be redefined, not merely as a circulation artery but as a layered series of spaces that provide varying degrees of privacy, with alcoves where residents can rest and connect. This could be achieved by recessing some walls or creating balconies or sky gardens that enrich the living experience.

Connecting with the Public Realm

Other proposed schemes by the students looked outward, showing how senior housing could better connect with its surroundings. One proposed a pedestrian bridge threading through the school hall to link developments on both sides of the road, turning the hall into a lively social hub. Another extended a nearby park into the site, transforming the ground plane into a recreational landscape. These interventions addressed the risk of isolation for seniors with reduced mobility. Similar thinking has shaped CPG’s own assisted living project now under construction, where a fenceless design allows residents and neighbours to interact freely in an adjoining community park.

The Psychology of Co-living

One scheme, titled Design for Introverts, examined how communal housing could be made less stressful for those uncomfortable with constant interaction. Large communal facilities such as dining areas were paired with adjoining smaller rooms where more reserved residents could retreat. Corridors were kept shorter to limit the number of neighbours one might encounter, while recessed entrance thresholds provided an added sense of privacy. Together, these ideas demonstrated how sensitive design can address not only physical needs but also the social and emotional comfort of residents.

Building on this, the panel shared the view that while such approaches show promise, the sociological aspects of intergenerational co-living in Singapore’s context will need careful study. The dynamics of mixing seniors with younger people, such as working adults and students, hold exciting potential and could be mutually beneficial. Yet, as with any new model, unintended consequences may arise and will require thoughtful adjustment in planning and design. “The architect in this field must think not only as a designer but also as a sociologist,” said Peter.

Looking Ahead

While many of these concepts would require a greater degree of intervention than is commercially feasible today, they open valuable avenues for future thinking. The exercise demonstrated how bold ideas can inspire more inclusive and connected ways of living. Importantly, the explorations by SUTD students resonate with the themes of DRO’s Design for Senior Co-living research, which emphasises the role of common spaces, circulation, and shared interfaces in nurturing social bonds and well-being. By linking academic exploration with practical research, CPG underscores its commitment to reimagining senior housing models that balance innovation, feasibility, and social value. With the right frameworks and openness to new possibilities, some of these ideas may well inform Singapore’s built environment in the years ahead.

The design studio at SUTD was conducted as part of CPG DRO’s research into co-living typologies for seniors.